In his novels, master of simple and pointed satirical and science fiction prose, Kurt Vonnegut, is usually piecing together the seemingly-trivial happenings to point to something huge. He is as humble as they come, though there is a great daring in his major works, like "Mother Night", where a simple playwright becomes an American double-agent during WWII, tried as a Nazi, sentenced to death, and, well, his demise is something legendary to me. That's heavy stuff, but there are the light-hearted commentaries, the yearning for a simpler time, the famous Vonnegut examinations of Nihilism through unlikely encounters that really help give form to the heavier commentaries of pretending to be what you are not until you are no longer pretending. He is able to mesh, throughout a book, the delicate parts of the soul, the seemingly meaningless meetings and events of life, and tie them into something enormous.

So it is that I couldn't resist a collection of short stories from the great American author. "Welcome to the Monkey House" contains 25 of'um, published primarily in the 50s, stories Vonnegut used to fund his bigger works (as he says). They range from sentimental little wisps of words ("Long Walk To Forever", "The Kid Nobody Could Handle") to more weighty experiments in human nature and ever-evolving technology that are shockingly relevant 50 years later ("Report on the Barnhouse Effect", "EPICAC"), and so on. It is pure Vonnegut, really, in shortened form, with the usual pinch of bitterness toward a world that never looks back, but a lot of optimism for the true souls of conscientious human beings.

It is the little bits of romantic angst and simpler sentiments that I shouldn't be so surprised about, but completely am. "Long Walk To Forever" is but seven/eight pages of a young man, who just went AWOL, tracking down the woman he had loved forever, who was about to be married. She denies, he persists, he relents, she desires. And in a sea of profoundly affecting final lines that Vonnegut is so perfect at, "She ran to him, put her arms around him, could not speak," is lovely, yet indeed, bordering on tacky. It's still so Vonnegut, though, and he was a man without caring for the concept of "guilty pleasures", after all, his most famous recurring character, Kilgore Trout, was the king of writing guilty pleasures, and Vonnegut adored him, I assume, as much as nearly any living person. Other stories, such as the commentary of reserving judgement and working to see through to someone's happiness, no matter how crazy it may seem, such as "More Stately Mansions", or the angst-ridden criticism on selling-out with "Deer in the Works" (with the most beautiful picture of man walking back into the woods with the deer caught in an enormous industrial park, as was he) are a bit less sappy, while still painting the poignant picture of what life was all about according to Vonnegut.

There is still quite a bit of sci-fi in Vonnegut's shorter works, too, as he constructs scenarios of technological progress and its undpredictable results. "EPICAC" may be my favorite of the collection, as man creates a monster computer, then our protagonist, lovestruck, tries to get EPICAC to write him poems for this woman he is courting. Then EPICAC, in a great turn, falls in love with the woman and thinks she is to marry him, and when he is taught the concept of fate in love and his limitations in this realm as a machine, he shorts himself as his final act. It's twisted, off-the-wall, and oddly touching. Poor guy never asked to learn about love, he was just supposed to crack equations. "Harrison Bergeron", on the other hand, is a cautionary tale of what equality really means, as well as another twistedly moving scene of free expression in the face of fascism. "Unready To Wear" may be the most beautifully striking of Vonnegut's sci-fi short compositions, where we see people advance in a positive way, to the point some have shed their burden of a body to just exist as a psyche whipping from place to place. Of course, they are under attack by the rest of human beings who view this progress as elitism, a condescension on what you are supposed to be as a human, a dissent from greatness. But those people, with their wars and limitations, cannot conceal, nor near understand, liberation.

Yes, Vonnegut had some ideas, and I had no idea to expect "Welcome to the Monkey House" to be a virtual notebook of stunning concepts in a shorter form. Everything here is fully developed and reaches its intellectual and emotional target. His prose are on-par with the likes of his best and most famous works. I can't help but to still feel more fulfilled with the likes of "God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater" or "Slaughterhouse-Five", because you get to be with the characters longer and Vonnegut can draw up the most out-of-leftfield parallel narratives and make them work to magnificent heights, but that is not what "Welcome to the Monkey House" is all about. These works are 20-page-or-less hit-and-quit pieces of Vonnegut that every fan of his cannot do without. Forget Mr. Rosewater, God bless you Mr. Vonnegut!

"'I don't want to be a machine, and I don't want to think about war,' EPICAC had written after Pat's and my light-hearted departure. 'I want to be made of protoplasm and last forever so Pat will love me. But Fate has made me a machine. That is the only problem I cannot solve. That is the only problem I want to solve. I can't go on this way.'"

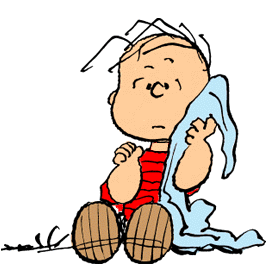

PS -- I picked the image that would probably have had Kurt Vonnegut on the floor in tears. That is, you know, if he didn't see it before he died. I have no clue. Here's a joke: Maybe I'll ask him when I see him again!

No comments:

Post a Comment